Climate Change’s Impact on US National Parks: A Comprehensive Look

The implications of climate change for US National Parks and Protected Areas are profound and multifaceted, threatening natural ecosystems, cultural resources, and visitor experiences through rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and increased extreme weather events.

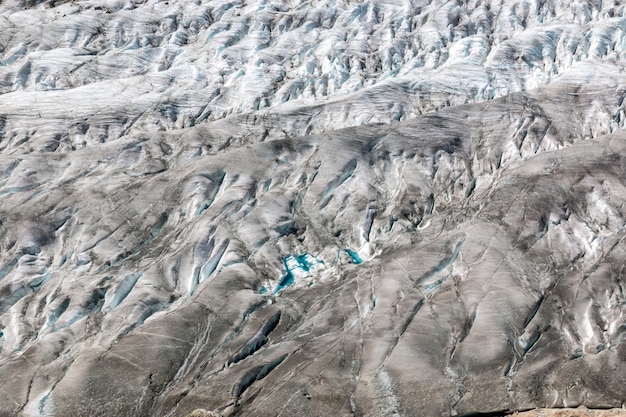

The majestic expanse of US National Parks and Protected Areas stands as a testament to natural beauty and biodiversity, yet these irreplaceable treasures face an existential threat. Understanding what are the implications of climate change for US National Parks and Protected Areas is crucial, as these iconic landscapes, from the glaciated peaks of Glacier National Park to the delicate coral reefs of Biscayne National Park, are on the front lines of a rapidly changing climate.

Rising Temperatures and Shifting Ecosystems

The undeniable trend of global warming is profoundly altering the fundamental characteristics of our national parks. Increased temperatures are not mere inconveniences; they are drivers of systemic change, prompting shifts in ecological zones and threatening the delicate balance of long-established plant and animal communities.

As mercury levels climb, many species are compelled to migrate to higher altitudes or latitudes in search of cooler, more suitable habitats. This phenomenon, known as climate-induced range shift, can lead to the fragmentation of populations, reduced genetic diversity, and, in some cases, local extinctions when suitable new territories are unavailable or blocked by human development.

Impact on Flora and Fauna

The plant life within national parks is exceptionally vulnerable to temperature shifts. Specific species adapted to narrow temperature ranges, such as alpine flowers or certain tree species, struggle to survive when conditions deviate from their historical norms. This can lead to a domino effect throughout the food web, impacting herbivores that rely on specific plants, and subsequently, the predators that hunt them.

- Altered Growing Seasons: Warmer temperatures can disrupt the timing of plant flowering and fruiting, affecting pollinators and seed dispersal.

- Increased Pest Outbreaks: Milder winters fail to kill off insect pests, leading to more frequent and severe infestations that decimate forests, such as pine beetle outbreaks.

- Water Stress on Vegetation: Higher temperatures exacerbate drought conditions by increasing evaporation rates, leading to more plant stress and mortality.

Animals also face significant challenges. Changes in migratory patterns, breeding cycles, and food availability are common. Species dependent on specific climate-dependent features, like pikas that rely on cool, moist rock crevices, are particularly at risk as their preferred habitats shrink or disappear entirely. The interconnectedness of these ecosystems means that the stress on one component can ripple through the entire system, leading to widespread disruption.

The warming climate also puts stress on aquatic systems, with rising water temperatures affecting fish populations, particularly cold-water species like trout, and altering the chemistry of lakes and streams. These changes can degrade water quality, impacting not only the aquatic life but also the availability of clean water for wildlife and visitors.

Altered Precipitation Patterns and Water Scarcity

Climate change is not just about rising temperatures; it also fundamentally reshapes precipitation patterns. Some regions experience more intense rainfall events, leading to increased flooding and erosion, while others face prolonged and severe droughts. These shifts directly impact the hydrological cycles that sustain national parks, influencing everything from river flows to groundwater reserves.

The erratic nature of precipitation poses significant management challenges for park authorities. Managing water resources becomes more complex when historical patterns are no longer reliable, requiring adaptive strategies for everything from firefighting to maintaining visitor amenities.

Consequences for Hydrology and Landscapes

In many western US national parks, snowpack is a critical natural reservoir, releasing water gradually throughout the spring and summer. Warmer temperatures are leading to earlier snowmelt and a reduction in the overall snowpack, drastically reducing water availability during the driest months. This early melt overwhelms river systems initially, followed by prolonged periods of low flow or even dry streambeds.

- Increased Wildfire Risk: Drier vegetation and extended periods of drought create ideal conditions for more frequent and intense wildfires, devastating ecosystems and infrastructure.

- Erosion and Landslides: Intense rainfall events on parched or fire-damaged landscapes can lead to severe soil erosion, flash floods, and landslides, reshaping terrain and damaging trails and roads.

- Impact on Aquatic Ecosystems: Reduced water flow and higher temperatures in rivers and lakes stress aquatic life, leading to declines in fish populations, algal blooms, and compromised water quality.

The shift in precipitation patterns also affects groundwater recharge, impacting springs and wetlands that are vital habitats for many species. Iconic waterfalls might diminish, and ephemeral pools, crucial for amphibian breeding, could disappear entirely. Managing these water stresses requires innovative solutions, including water conservation efforts, restoration of natural floodplains, and the careful monitoring of hydrological changes.

These changes in water availability and distribution not only threaten native species but also make it harder for non-native invasive species to be controlled, as their hardiness often allows them to thrive in disrupted environments. The combined effect of water scarcity and invasive species represents a complex threat to the ecological integrity of these protected areas.

Increased Frequency and Intensity of Extreme Weather Events

A hallmark of a changing climate is the escalation of extreme weather events, which are becoming more frequent, more intense, or both. For US National Parks and Protected Areas, this translates into a heightened risk from phenomena such as severe droughts, prolonged heatwaves, devastating wildfires, and powerful storms. These events inflict immediate and often catastrophic damage, with long-lasting implications for ecosystems and infrastructure.

The ability of park systems to recover from these shocks is being tested, as the intervals between extreme events shorten, leaving less time for natural regeneration or human-led restoration efforts. This continuous stress can push ecosystems beyond their natural resilience thresholds.

Wildfires: A Growing Threat

Wildfires, a natural component of many forest ecosystems, are now occurring with unprecedented intensity and scale due to hotter, drier conditions. Mega-fires consume vast tracts of land, destroying habitats, altering soil composition, and releasing significant amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, contributing further to climate change.

- Ecological Devastation: Fires can wipe out entire populations of slow-moving animals, sterilize soil, and destroy ancient trees, fundamentally changing the landscape for decades.

- Air Quality Degradation: Smoke plumes from large fires can travel hundreds of miles, impacting air quality in distant urban areas and posing health risks to visitors and residents.

- Infrastructure Damage: Roads, trails, visitor centers, and historical structures are vulnerable to fire damage, requiring costly repairs and prolonged closures.

The management of wildfires within national parks has become an increasingly complex challenge, balancing the ecological need for fire with the imperative to protect human life and property. Prescribed burns are a tool, but their application is increasingly constrained by volatile weather conditions and the sheer scale of the fire risk.

Beyond fires, other extreme events like powerful hurricanes impacting coastal parks or intense blizzards in mountain regions can cause widespread tree felling, coastal erosion, and damage to facilities. The cumulative effect of these repeated impacts significantly degrades the visitor experience and strains park management resources.

Impacts on Cultural and Historical Resources

The US National Parks system is not just about natural landscapes; it also safeguards an invaluable array of cultural and historical resources, from ancient cliff dwellings and archaeological sites to historic structures and battlefields. Climate change poses a unique and often overlooked threat to these irreplaceable artifacts of human history and heritage.

These cultural resources are static and cannot adapt to changing environmental conditions in the same way living organisms might. Their vulnerability stems from direct exposure to shifting weather patterns, sea-level rise, and the degradation of the very natural processes that historically preserved them.

Threats to Archeological Sites and Structures

Many archaeological sites are nestled in environments that have been stable for centuries, allowing their delicate structures and artifacts to survive. Increased rainfall, intensified flooding, or prolonged droughts can dramatically alter the soil stability, leading to erosion, exposure, or disintegration of buried remains.

- Erosion and Exposure: Increased storm intensity washes away protective layers of soil, exposing archaeological features to degradation from wind, sun, and further erosion.

- Structural Damage: Historic buildings, especially those made of mud, adobe, or wood, are susceptible to damage from extreme moisture, rot, or conversely, desiccation and cracking from prolonged dry spells.

- Coastal Submergence: For sites located on coastlines or low-lying areas, rising sea levels and storm surges threaten to inundate and permanently destroy archaeological sites and historic structures.

For example, some of the ancient pueblo sites in the Southwest, built of adobe, are experiencing accelerated deterioration due to changes in precipitation patterns—either too much moisture causing erosion or too little causing the material to crack. Native American sacred sites, often tied to specific landscape features, are also at risk when those features are altered or destroyed by climate impacts.

The challenge for park managers is immense, requiring innovative conservation methods, detailed monitoring, and sometimes, the difficult decision to triage resources or even consider relocating artifacts or stabilize structures against the backdrop of an inexorably changing climate. Documenting these sites before they are lost is also a critical, though tragic, necessity.

Challenges to Visitor Experience and Park Operations

The primary purpose of national parks, beyond conservation, is to provide inspiration, education, and recreation for visitors. Climate change directly impacts the quality and availability of these experiences, posing significant operational challenges for park managers and impacting the broader tourism economy that often supports gateway communities.

As the effects of climate change become more pronounced, the traditional allure of certain park activities may diminish, and new safety concerns for visitors will emerge. This necessitates a reevaluation of how parks are accessed, managed, and enjoyed by the public.

Impact on Recreation and Safety

Warmer temperatures and altered seasons directly affect popular recreational activities. Skiing and snowshoeing seasons shorten in winter, while summer activities like hiking and camping are increasingly marred by extreme heat warnings or air quality alerts due to wildfire smoke. Water-based activities can be curtailed by low river levels or excessive algal blooms.

- Reduced Accessibility: Damage to roads and trails from floods, landslides, or fires can lead to prolonged closures, limiting access to popular areas or entire parks.

- Health Risks for Visitors: Increased heatstroke risk, exposure to wildfire smoke, and potential for encountering wildlife stressed by environmental changes pose direct threats to visitor health.

- Changes in Flora and Fauna Viewing: Iconic wildlife might shift their ranges, migratory patterns change, or specific plant blooms might be altered, diminishing unique viewing opportunities.

Park operations are strained by the need to respond to climate impacts. Maintaining infrastructure becomes more expensive and challenging in the face of repeated damage. Adapting to fluctuating water availability, managing increased wildfire risks, and educating visitors about new hazards require significant resources and staff training.

Furthermore, climate change could lead to increased visitor pressure on less-affected parks, potentially exacerbating overcrowding and environmental degradation in those areas. Park management must balance conservation efforts with the continued provision of a meaningful and safe visitor experience in a rapidly changing world.

Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies

In the face of these profound challenges, the US National Park Service (NPS) and various partners are actively pursuing a range of adaptation and mitigation strategies to build resilience within the parks and address the root causes of climate change. These efforts are multi-faceted, requiring scientific research, policy changes, active resource management, and public engagement.

The goal is not merely to react to climate impacts but to proactively plan for future conditions, protecting both natural and cultural resources while ensuring the parks remain accessible and inspiring for generations to come. This approach acknowledges that a combination of local action and global efforts is essential.

Strategies for Resilience and Conservation

Adaptation strategies focus on reducing vulnerability to climate impacts and improving the capacity of ecosystems and infrastructure to cope with change. This often involves science-informed interventions, such as restoring natural processes that enhance resilience, like healthy river flows or diverse forest structures.

- Ecological Restoration: Projects to restore wetlands, reforest fire-damaged areas with climate-resilient species, or remove invasive species create healthier ecosystems better able to withstand stress.

- Infrastructure Hardening: Upgrading roads, bridges, and buildings to withstand more extreme weather events, or relocating vulnerable infrastructure away from floodplains or coastlines.

- Enhanced Monitoring: Implementing sophisticated monitoring systems to track changes in wildlife populations, water levels, and vegetation health, providing data for adaptive management.

Mitigation efforts, while often beyond the direct control of park managers, involve contributing to the global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. The NPS aims to reduce its own carbon footprint through energy efficiency, renewable energy adoption, and sustainable transportation within parks.

Collaboration with adjacent landowners, tribal nations, and international partners is also crucial, as climate change impacts span beyond park boundaries. Shared knowledge, coordinated conservation, and collective advocacy for climate action are vital components of a comprehensive response.

Ultimately, the long-term viability of US National Parks hinges on both their ability to adapt to unavoidable changes and humanity’s collective success in mitigating further global warming. These protected areas serve as living laboratories and poignant reminders of what is at stake, urging us to safeguard them for their intrinsic value and their critical role in our shared natural heritage.

| Key Aspect | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| 🌡️ Ecosystem Shifts | Rising temperatures force species migration and alter plant growing seasons, stressing biodiversity. |

| 💧 Water Scarcity | Changes in snowpack and precipitation lead to droughts and increased wildfire risk. |

| 🏛️ Cultural Heritage at Risk | Historic sites face erosion, structural damage, and submersion from extreme weather and sea-level rise. |

| ⛔ Visitor Experience & Operations | Recreation is impacted by heat, smoke, and closures; park management faces infrastructure and safety challenges. |

Frequently Asked Questions About Climate Change’s Impact on US National Parks

▼

Climate change directly threatens biodiversity by altering temperature and precipitation patterns, forcing species to shift their geographical ranges or face extinction. Habitats shrink, food sources become scarce, and increased extreme weather events disrupt delicate ecosystems, challenging the survival of both flora and fauna within the parks.

▼

Yes, cultural and historical sites are highly vulnerable. Changes in precipitation, increased erosion, and rising sea levels can directly destroy ancient structures, archaeological remains, and historic landscapes. Unlike natural systems, these resources cannot relocate, making preservation efforts challenging and requiring extensive conservation strategies.

▼

Primary operational challenges include managing increased wildfire frequency and intensity, addressing water scarcity for both ecosystems and visitors, repairing infrastructure damaged by extreme weather, and ensuring visitor safety amidst new environmental hazards. These impacts strain resources and demand adaptive management strategies from park authorities.

▼

Climate change is visibly altering iconic landscapes through glacier melt (e.g., Glacier National Park), increased frequency of large-scale wildfires, desertification, and coastal erosion. These changes degrade natural beauty, impact the availability of specific recreational opportunities, and threaten unique geological formations, forever reshaping familiar vistas.

▼

Protection strategies involve both adaptation and mitigation. Adaptation includes ecological restoration, hardening infrastructure, and enhancing biodiversity monitoring. Mitigation efforts focus on reducing the parks’ own carbon footprints through energy efficiency and renewable energy, alongside advocacy for broader climate action to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

Conclusion

The implications of climate change for US National Parks and Protected Areas are far-reaching, transforming their very essence from the highest peaks to the deepest canyons and along the fragile coastlines. These revered landscapes and their embedded cultural histories face unprecedented threats that demand immediate and sustained attention. The intricate web of ecosystems is under immense pressure from rising temperatures, altered water cycles, and intensifying extreme weather events, leading to shifts in biodiversity and widespread habitat degradation.

Moreover, the preservation of our shared heritage, embodied in the historic structures and archaeological sites within these parks, is also precarious, with irreplaceable cultural resources vulnerable to the whims of an unpredictable climate. The very experiences that draw millions to these natural wonders are being reshaped, impacting visitor enjoyment and placing significant strain on park management and operations. As we look to the future, the fate of these protected areas hinges on a comprehensive and collaborative response that combines robust scientific research with proactive adaptation strategies. Ultimately, safeguarding these national treasures requires a collective commitment to address the underlying causes of climate change, ensuring that their beauty and ecological integrity endure for generations to come.