Clean Water Act Changes & US Agricultural Runoff Impact

Proposed changes to the Clean Water Act could significantly alter how agricultural runoff, a major nonpoint source of pollution, is regulated in the US, potentially affecting water quality, farming practices, and the balance between environmental protection and agricultural productivity.

Understanding how will the proposed changes to the Clean Water Act affect agricultural runoff in the US is crucial for anyone invested in environmental policy, sustainable agriculture, and public health. This complex issue impacts vast landscapes, diverse communities, and the very health of our nation’s waterways.

The Clean Water Act: A Legacy of Protection

The Clean Water Act (CWA), originally enacted in 1972, stands as a landmark piece of legislation designed to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation’s waters. Its primary goal was to make all US waters “fishable and swimmable” by eliminating pollutant discharges. For decades, the CWA has been a cornerstone of environmental protection, leading to significant improvements in water quality across the country.

However, the application of the CWA, particularly concerning diffuse sources of pollution like agricultural runoff, has always been a point of contention. The Act primarily focuses on point source discharges, such as those from industrial facilities and municipal wastewater treatment plants, which are easier to identify and regulate through permits. Nonpoint source pollution, which includes agricultural runoff, stormwater runoff, and atmospheric deposition, is much more challenging to control due to its widespread and decentralized nature.

The original intent and subsequent interpretations have led to a patchwork of regulations and enforcement, often leaving significant gaps in addressing agricultural pollution. This historical context is vital when examining any proposed changes, as they invariably seek to either strengthen or relax these existing frameworks, with profound implications for water bodies nationwide.

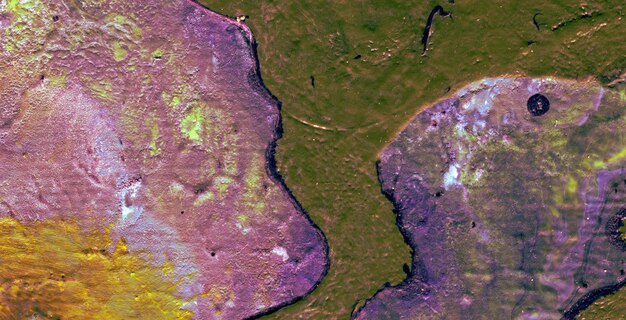

Defining Agricultural Runoff and Its Impacts

Agricultural runoff refers to water from irrigation, rain, or melting snow that flows over agricultural fields, picking up pollutants such as fertilizers, pesticides, animal waste, and eroded soil, eventually carrying them into rivers, lakes, and oceans. These pollutants can have devastating effects on aquatic ecosystems and human health.

- Nutrient Pollution: Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers can lead to algal blooms, which deplete oxygen in water (hypoxia), creating “dead zones” where aquatic life cannot survive.

- Pesticide Contamination: These chemicals can be toxic to aquatic organisms, accumulate in the food chain, and pose risks to human health through contaminated drinking water.

- Sedimentation: Eroded soil particles increase turbidity, reducing light penetration for aquatic plants, and smothering fish spawning grounds and bottom-dwelling organisms.

- Pathogens: Animal waste can introduce bacteria and viruses, making water unsafe for recreation and drinking.

Addressing these impacts requires a comprehensive approach that considers both regulatory mechanisms and voluntary conservation practices. The effectiveness of the CWA in mitigating these problems hinges on its scope and the willingness of enforcement agencies to apply its provisions to agricultural activities.

The economic implications of agricultural runoff are also substantial, affecting fisheries, tourism, and drinking water treatment costs. Therefore, any legislative changes must balance environmental protection with the economic viability of the agricultural sector, which is a significant part of the US economy. This delicate balance often defines the political landscape surrounding water policy.

Key Proposed Changes to the Clean Water Act

Recent proposals concerning the Clean Water Act often revolve around the definition of “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS), which determines the geographic jurisdiction of the CWA. Shifting this definition can either expand or contract federal authority over certain wetlands and ephemeral streams, directly impacting how agricultural runoff sources are regulated.

Historically, the definition of WOTUS has been a source of significant legal and political debate, leading to multiple rule changes and Supreme Court cases. Each administration typically seeks to interpret WOTUS in a way that aligns with its environmental or economic priorities. The current landscape suggests a move towards a clearer, potentially narrower, definition compared to previous expansive interpretations.

Another area of proposed change involves the scope of exemptions for agricultural activities. The CWA currently exempts “normal farming, silviculture, and ranching activities” from certain permitting requirements for dredge and fill operations. Future changes might seek to clarify or expand these exemptions, potentially reducing the regulatory burden on farmers but also lessening environmental oversight.

Defining “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS)

The definition of WOTUS is perhaps the most critical aspect influencing the CWA’s reach. A broader definition includes more wetlands, ephemeral streams, and ditches, thus extending federal jurisdiction and potential regulatory requirements to more agricultural lands. Conversely, a narrower definition limits federal oversight, often relying more on state-level regulation.

For example, rules have varied from defining WOTUS broadly to including relatively isolated wet areas, to more restrictive definitions that require a direct and continuous surface connection to traditionally navigable waters. Each proposed rule brings a new set of legal challenges and practical implications for farmers and environmental agencies alike. The ongoing legal battles underscore the deep divisions on this issue.

The implications for agricultural runoff are direct: if a ditch or wetland on a farm is considered a “Water of the United States,” then discharges into it might fall under CWA permitting requirements. If it’s not, then runoff from that land might be unregulated at the federal level, relying solely on state or voluntary best management practices.

Changes to Agricultural Exemptions

The CWA includes specific exemptions for routine agricultural activities, such as plowing, planting, and cultivating, from the Section 404 permitting requirements for dredge and fill materials. These exemptions are intended to avoid hindering normal farming operations with bureaucratic hurdles. However, the interpretation of “normal” and the distinction between exempted and non-exempted activities can be complex.

Proposed changes might seek to refine these exemptions, for instance, by clarifying what constitutes “normal farming” or by addressing activities that could be seen as expanding agricultural operations rather than maintaining existing ones. Any such clarification could either reduce ambiguity for farmers or introduce new regulatory obligations.

Another potential area of change involves concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). While CAFOs are generally considered point sources and thus subject to CWA permitting, there have been ongoing debates about how fully their discharges are regulated, particularly in cases of overland flow or spills. Future proposals could tighten or loosen these specific regulations, impacting the management of manure runoff.

The interplay between these definitional and exemption changes forms the core of how the CWA’s regulatory power over agricultural runoff would shift. These aren’t just legalistic nuances; they represent fundamental decisions about who holds authority and what level of environmental protection is provided.

Potential Ramifications for Agricultural Runoff Management

The direct impact of proposed CWA changes on agricultural runoff management is multifaceted, influencing everything from the adoption of conservation practices to the economic burdens faced by farmers. A less stringent CWA could theoretically reduce the immediate regulatory pressure on agricultural operations. This might translate to lower compliance costs for some farmers who are not currently investing heavily in runoff mitigation strategies. However, this reduction in direct costs could come at a much higher price for the environment and public health.

Without clear federal oversight, water quality could deteriorate more rapidly in agricultural regions. States might step in with their own regulations, but these can vary significantly in scope and enforcement, leading to an uneven playing field and potentially creating “pollution havens.” This fragmented approach could undermine the broader goals of water quality improvement outlined in the CWA.

Furthermore, the long-term economic consequences for the agricultural sector itself could be negative. Degradation of water quality can affect the availability of clean water for irrigation, increase the cost of water treatment for rural communities, and damage aquatic ecosystems that support valuable fisheries and recreational industries. These indirect costs may eventually outweigh any short-term savings from reduced regulation.

Impact on Farmers and Farming Practices

For individual farmers, the proposed changes could either ease regulatory burdens or create new uncertainties. If WOTUS is narrowed and agricultural exemptions expanded, some farmers might face less federal scrutiny regarding their runoff. This could allow greater flexibility in land management decisions, potentially reducing costs associated with implementing certain best management practices (BMPs).

Conversely, less federal oversight might shift the burden to state and local governments, which may or may not have the resources or political will to implement effective runoff control programs. Farmers might then face a patchwork of differing state regulations, complicating compliance for those operating across state lines.

- Reduced Direct Compliance Costs: Less stringent federal rules might mean fewer requirements for permits or specific runoff control measures for certain operations.

- Increased Voluntary Adoption: Without direct mandates, reliance on voluntary incentive programs for conservation practices might increase.

- Uncertainty and Variability: A shifting regulatory landscape can create uncertainty for long-term planning, and reliance on state laws can lead to significant national variability in water quality outcomes.

The emphasis could shift from regulatory compliance to market-based incentives or voluntary programs championed by groups like the USDA. While these programs are valuable, their effectiveness often depends on funding levels and farmer participation rates, which can fluctuate.

Environmental and Public Health Consequences

The primary concern with a relaxed CWA is the potential for significant environmental degradation. Increased agricultural runoff, unchecked by federal standards, could lead to more widespread nutrient pollution, exacerbating algal blooms and creating larger dead zones in critical water bodies like the Gulf of Mexico and the Great Lakes. This has direct impacts on biodiversity, disrupting food chains and leading to species loss.

Public health is also at stake. Contaminated drinking water sources from nitrates, pesticides, and pathogens present serious health risks, necessitating more expensive and complex water treatment processes for municipalities. Recreational activities like swimming and fishing could be curtailed due to unsafe water conditions, impacting local economies and quality of life.

- Worsening Water Quality: Increased nutrient and pesticide loads in rivers, lakes, and coastal waters.

- Ecosystem Degradation: Expansion of dead zones, loss of biodiversity, and impacts on aquatic food webs.

- Human Health Risks: Contaminated drinking water and reduced opportunities for safe water recreation.

The long-term effects of unchecked agricultural runoff can be cumulative and difficult to reverse, making proactive regulation a critical component of environmental stewardship. The balance between agricultural productivity and environmental protection is a delicate one, and the proposed changes will undoubtedly shift this equilibrium.

The Role of Voluntary Conservation Programs

Even with strict regulations, voluntary conservation programs play a crucial role in addressing agricultural runoff. These programs, often administered by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), provide financial and technical assistance to farmers who adopt practices that conserve natural resources and improve environmental quality. Programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) offer cost-sharing and incentives for practices such as no-till farming, cover cropping, nutrient management, and riparian buffers.

The idea behind these programs is to encourage adoption of practices that go beyond minimal regulatory compliance, fostering a deeper commitment to stewardship. They acknowledge that farming is a complex practice and that a one-size-fits-all regulatory approach may not always be the most effective or economically viable solution for every farm.

In a scenario where CWA regulations are loosened, the importance and reliance on these voluntary programs could increase significantly. They would likely become the primary mechanism for driving positive environmental outcomes in agricultural landscapes, putting more pressure on their funding levels, administration, and outreach efforts.

USDA Programs and Their Effectiveness

The USDA’s suite of conservation programs represents the largest source of federal funding for agricultural conservation. EQIP, for instance, helps farmers plan and implement conservation practices that address specific resource concerns like soil erosion, water quality, and habitat preservation. CSP rewards farmers for existing conservation efforts and for adopting new, advanced practices.

The effectiveness of these programs is often measured by the environmental benefits achieved and the participation rates among farmers. While they have demonstrably led to improvements in localized areas, their impact on a broader scale can be limited by funding availability, the voluntary nature of participation, and the specific needs of different agricultural regions.

Success often depends on:

- Adequate Funding: Ensuring sufficient financial incentives to make conservation practices economically attractive for farmers.

- Technical Assistance: Providing expertise to help farmers design and implement complex conservation systems effectively.

- Targeted Outreach: Reaching farmers in high-priority watersheds or those facing specific environmental challenges.

If proposed CWA changes reduce regulatory drivers, these programs would need to redouble their efforts to encourage adoption through incentives and education, rather than solely relying on compliance.

Balancing Regulation and Incentives

The debate over agricultural runoff almost always boils down to finding the right balance between regulatory mandates and voluntary incentives. Regulations provide a baseline level of protection and ensure a degree of accountability, especially for significant contributors to pollution. Incentives, on the other hand, encourage innovation and adoption of practices tailored to specific farm conditions, often exceeding minimal compliance.

A synergistic approach, where robust regulations are complemented by well-funded and well-designed incentive programs, is often considered the most effective way to address nonpoint source pollution. Regulations can drive initial compliance, while incentives foster a culture of continuous improvement and environmental stewardship.

If proposed CWA changes swing the pendulum heavily towards voluntary approaches by narrowing regulatory scope, there is a risk that environmental progress might slow or even reverse without a substantial increase in investment and effectiveness of these incentive programs. The question becomes whether voluntary efforts alone can achieve the scale of change needed to protect and restore the nation’s waters.

This balance point is critical for the long-term sustainability of both agriculture and the environment. Policy decisions must consider how these two approaches interact and how they collectively advance the goal of cleaner water.

State and Local Responses to Federal Shifts

In the event of significant federal shifts in Clean Water Act enforcement and scope, state and local governments will likely play a more prominent role in regulating agricultural runoff. States historically have had primary authority over land use and water quality within their borders, and many already implement a variety of programs to address nonpoint source pollution. However, the capacity and commitment of states vary widely across the US.

Some states have robust environmental agencies and progressive water quality standards, while others may have limited resources or face political resistance to implementing stringent agricultural regulations. This disparity can lead to a fragmented national approach to water quality, where some watersheds see improvements while others continue to degrade.

Local initiatives, such as watershed-based planning and ordinances at the county or municipal level, also become increasingly important. These efforts can be highly effective because they are tailored to specific local conditions and often involve direct stakeholder engagement. However, their impact is limited by their geographic scope and depend heavily on local political will and funding.

Varying State Regulations and Programs

States employ a diverse range of strategies to manage agricultural runoff:

- Nutrient Management Plans: Many states require or incentivize farmers to develop plans that optimize fertilizer application to reduce nutrient losses.

- Erosion Control Laws: Some states have mandatory no-till or cover crop requirements in sensitive areas.

- Watershed-Specific Initiatives: Programs focused on particular rivers, lakes, or coastal areas that are heavily impacted by agricultural pollution.

- Permitting Programs: A few states have broader permitting requirements for certain agricultural operations that go beyond the federal CWA.

The effectiveness of these programs is often tied to their enforcement mechanisms and the availability of state-level funding for technical assistance and incentives. A less active federal CWA could spur some states to strengthen their own regulations, particularly those that are already dealing with severe water quality issues. However, it could also allow other states to maintain a less rigorous approach, potentially creating advantages for agricultural producers in those areas but at an environmental cost.

Challenges and Opportunities for Local Action

Local governments and community groups are often on the front lines of dealing with the immediate impacts of agricultural runoff. This proximity can provide unique opportunities for targeted solutions and direct engagement with farmers. Challenges, however, include limited financial and technical resources, the difficulty of regulating nonpoint sources at a hyper-local level, and potential conflicts with state or federal preemption.

Opportunities for local action include:

- Local Ordinances: Implementing zoning or environmental ordinances specific to agricultural areas, such as buffer strip requirements or setback rules for livestock operations.

- Community Partnerships: Forming collaborations between farmers, conservation groups, and local agencies to develop and implement watershed improvement projects.

- Public Education: Raising awareness among local residents about the connection between land use and water quality, fostering a sense of shared responsibility.

While local efforts are crucial, they are rarely sufficient to address large-scale water quality problems on their own. A strong federal framework provides a necessary baseline and can facilitate coordination across jurisdictional boundaries. Without it, the burden on state and local entities, already stretched thin, could become overwhelming, making the goal of consistently clean water across the nation much more elusive.

The Debate: Economic Efficiency vs. Environmental Imperatives

At the heart of the proposed changes to the Clean Water Act, particularly as they pertain to agricultural runoff, lies a fundamental tension between economic efficiency in agricultural production and pressing environmental imperatives. Agriculture is a cornerstone of the US economy, providing food, fiber, and fuel, and supporting millions of jobs. Implementing environmental regulations, especially those targeting nonpoint source pollution, often entails compliance costs for farmers, which can include investments in new equipment, changes in practices, or reduced crop yields if certain land is taken out of production for conservation purposes. These costs are often cited by agricultural stakeholders as undue burdens that can threaten the competitiveness and profitability of farming operations.

On the other hand, advocates for stricter environmental controls argue that the costs of inaction far outweigh the costs of compliance. Environmental degradation, such as widespread algal blooms, contaminated drinking water, and depleted fisheries, imposes significant economic burdens on society. These “externalities”—costs borne by society at large rather than by the individual polluter—include increased water treatment expenses, declines in tourism and recreational revenue, and impacts on public health. Moreover, a healthy environment is increasingly seen not just as an amenity but as a critical component of long-term economic sustainability, including the resilience of agricultural systems themselves.

The debate often centers on who should bear the cost of addressing agricultural runoff: the farmers who produce the food, the consumers who buy it, or the taxpayers through government subsidies and programs. Finding a policy solution that effectively balances these competing interests is one of the most significant challenges in environmental governance.

Arguments for Deregulation in Agriculture

Proponents of loosening CWA regulations for agriculture often emphasize several key arguments:

- Economic Burden: Strict regulations, especially those related to WOTUS definitions, can impose substantial compliance costs on farmers, particularly small and mid-sized operations, potentially leading to financial hardship and reduced competitiveness.

- Property Rights: Some argue that expansive federal control over private land, including wetlands and ephemeral streams, infringes on property rights and limits a farmer’s ability to maximize land use.

- Flexibility and Innovation: Less prescriptive regulations could allow farmers more flexibility to innovate and adopt conservation practices that are best suited to their specific operations and local environmental conditions, rather than being forced into one-size-fits-all solutions.

- State Authority: There is an argument that states are better equipped to understand and manage their local water resources and agricultural practices, making state-level regulation more appropriate than broad federal mandates.

This perspective often highlights the resilience and adaptability of the agricultural sector, suggesting that voluntary efforts and market-based solutions, rather than top-down federal mandates, are the most effective ways to achieve environmental goals without stifling economic growth. They also point to the difficulty of regulating nonpoint sources, arguing that the CWA was not originally designed for such diffuse pollution.

Arguments for Stronger Environmental Protection

Conversely, those advocating for robust CWA oversight on agricultural runoff emphasize the following:

- Public Health: Unchecked runoff poses significant risks to drinking water quality, leading to health issues from contaminants like nitrates and pathogens, and increasing the cost of municipal water treatment.

- Ecosystem Health: The widespread degradation of waterways from nutrient loading, sedimentation, and pesticides damages aquatic ecosystems, reducing biodiversity, impacting fisheries, and creating “dead zones.”

- Long-Term Sustainability: Protecting water quality is essential for the long-term sustainability of agriculture itself, as clean water is vital for irrigation and livestock. Degraded water resources can undermine future productivity.

- Equity: The environmental impacts of agricultural runoff often disproportionately affect downstream communities, including marginalized populations, who may bear the brunt of pollution and associated health risks. Federal regulation provides a uniform baseline of protection across states.

This viewpoint stresses that environmental protection is not a luxury but a necessity, and that the costs of environmental remediation and public health crises far outweigh the compliance costs of proactive regulation. They argue that a strong federal CWA is essential to prevent a race to the bottom among states and to ensure a cohesive national strategy for clean water, which is a shared resource transcending state boundaries. They also emphasize that the CWA’s mandate is to protect the nation’s waters, regardless of the source of pollution.

The Path Forward: Collaboration and Innovation

Addressing agricultural runoff effectively, regardless of how the Clean Water Act’s provisions evolve, will require a concerted effort of collaboration and innovation. The complexity of nonpoint source pollution means there is no single, simple solution. Instead, a multi-faceted approach involving various stakeholders is necessary to achieve sustainable outcomes for both agriculture and water quality. This approach must integrate scientific understanding, technological advancements, economic realities, and strong partnerships between government agencies, farmers, environmental groups, and local communities.

Innovation in agricultural practices is paramount. This includes developing and implementing advanced technologies for nutrient management, precision agriculture, and soil health improvement that not only reduce runoff but also enhance farm productivity and resilience. Collaboration, on the other hand, ensures that these innovations are adopted widely and that solutions are tailored to local contexts, respecting the diversity of farming systems and environmental conditions across the US.

The path forward cannot prioritize one interest group over another without significant societal cost. Instead, it must seek common ground, fostering solutions that are both environmentally beneficial and economically viable, ensuring that the burden of stewardship is shared equitably.

Technological Advancements in Runoff Control

Technological innovation offers promising avenues for mitigating agricultural runoff. Precision agriculture, using GPS, sensors, and data analytics, allows farmers to apply fertilizers and pesticides more efficiently, reducing excess application that can lead to runoff. For examples of applications:

- Variable-Rate Application: Applying inputs like fertilizer, seeds, and water at varying rates across a field based on soil conditions and crop needs, minimizing waste.

- Real-Time Nutrient Monitoring: Sensors that provide immediate data on soil nutrient levels, allowing farmers to adjust fertilizer use dynamically.

- Advanced Drainage Systems: Controlled subsurface drainage (drainage water management) that can store water in the soil profile during dry periods and reduce nutrient export during wet periods.

- Biofilters and Bioreactors: Engineered systems that use natural processes to remove nitrates and other pollutants from tile drain water before it enters waterways.

These technologies, combined with traditional best management practices (BMPs) like cover cropping, riparian buffers, and conservation tillage, offer powerful tools for reducing pollution. The challenge lies in making these technologies accessible and affordable for a wide range of farmers, which often requires continued research, development, and incentive programs.

Stakeholder Engagement and Adaptive Management

Effective management of agricultural runoff fundamentally depends on strong relationships and continuous dialogue among all stakeholders. This includes farmers, local water authorities, federal and state environmental agencies, conservation organizations, researchers, and local communities. Collaborative approaches, such as watershed planning groups and stakeholder roundtables, can help build consensus, share knowledge, and identify locally appropriate solutions.

Adaptive management—a systematic approach for improving resource management by learning from management outcomes—is particularly suited to complex environmental challenges like agricultural runoff. This involves:

- Setting Clear Goals: Defining specific, measurable water quality targets.

- Implementing Actions: Putting conservation practices and policies into place.

- Monitoring Progress: Regularly assessing water quality and environmental indicators.

- Evaluating Results: Analyzing data to determine the effectiveness of management actions.

- Adjusting Strategies: Modifying approaches based on what has been learned.

This iterative process allows policies and practices to evolve in response to new scientific information, changing agricultural conditions, and the effectiveness of previous interventions. It acknowledges that achieving clean water is an ongoing journey that requires flexibility and a willingness to learn and adapt.

Ultimately, the future of how the Clean Water Act affects agricultural runoff in the US will be shaped not just by legal definitions but by a commitment to shared responsibility, the continuous pursuit of innovative solutions, and the willingness of all parties to work together for the collective good of the nation’s waters.

| Key Aspect | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| 🌍 WOTUS Definition | Changes to “Waters of the United States” directly impact federal CWA jurisdiction over streams and wetlands crucial for agricultural runoff control. |

| 🌾 Farm Exemptions | Proposed rule modifications could clarify or expand CWA exemptions for normal farming, influencing regulatory burden and environmental outcomes. |

| 💧 Environmental Impacts | Less federal oversight could lead to increased nutrient pollution, algal blooms, dead zones, and risks to drinking water and aquatic ecosystems. |

| 🤝 Collaboration & Tech | Path forward relies on adopting innovative practices (e.g., precision agriculture) and fostering collaboration to balance economic and environmental needs. |

Frequently Asked Questions About Clean Water Act Changes and Agricultural Runoff

Agricultural runoff refers to water flowing from farms that carries pollutants like fertilizers, pesticides, and animal waste into waterways. It’s a significant concern because it contributes to nutrient pollution (leading to algal blooms and dead zones), pesticide contamination, and sedimentation, all of which harm aquatic ecosystems and can pose risks to human health through contaminated drinking water sources.

The WOTUS definition determines the federal Clean Water Act’s jurisdiction. If a ditch or wetland on a farm is considered a “Water of the United States,” then discharges into it become subject to federal regulation. A narrower WOTUS definition reduces federal oversight, potentially leaving more agricultural runoff sources to state-level regulation or voluntary measures, which vary widely.

No, not fully. The CWA already has specific exemptions for “normal farming activities” from certain permitting requirements. Proposed changes typically aim to clarify or adjust these existing exemptions or the scope of federal oversight. Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), for example, generally remain subject to permitting as point sources of pollution, regardless of WOTUS changes.

Voluntary programs, primarily through the USDA (like EQIP and CSP), provide financial and technical assistance to farmers for adopting beneficial practices (e.g., no-till, cover crops) that reduce runoff. These programs are crucial complements to regulation, and their importance might increase if federal regulatory oversight is reduced, necessitating greater reliance on incentives to drive environmental improvements.

Relaxing regulations could lead to a decline in water quality, expanding dead zones, increased public health risks from contaminated water, and diminished recreational opportunities. While potentially reducing short-term compliance costs for some farmers, the broader societal costs from environmental degradation could be substantial and difficult to reverse, impacting economies reliant on clean water and healthy ecosystems.

Conclusion

The proposed changes to the Clean Water Act concerning agricultural runoff in the US represent a critical juncture for environmental policy. How the “Waters of the United States” are defined and how agricultural exemptions are applied will profoundly influence water quality, farming practices, and the delicate balance between economic vitality and ecological health. While debates continue over the optimal blend of federal regulation, state authority, and voluntary initiatives, the imperative remains clear: protecting the nation’s water resources is a shared responsibility that demands comprehensive and adaptive strategies. The ultimate impact will depend not just on legislative texts, but on sustained collaboration and a commitment to innovation across all sectors.